Reinforcing Feedback Loops | Customers, Etc.

Learn to spot the growth patterns

This is the 4th post in a series on support systems (though it’s evolved to be more about business systems), which began with Your First Support Model. The most recent post in this series was about Modeling the Support System in HASH. The next post in this series is about Drift to Low Performance.

If you’ve worked on the customer support/experience side of the business like me, maybe there have been times where you’ve looked over at Sales and wondered why they seem to be having all the fun1. Sales get all kinds of training, they seem to hire at a crazy rate, they can buy any tools they want, and they even throw the best parties (at the end of the quarter, naturally, when they’re closing tons of deals—hopefully you’re invited).

Why?

Sales, the Reinforcing Feedback Loop

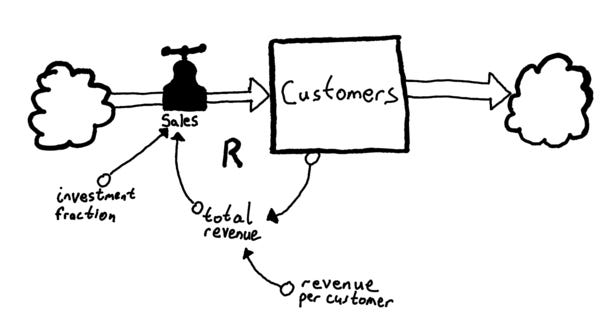

The reason sales gets so much attention is because it’s part of a positive reinforcing feedback loop. Each time you make a sale, you grow the number of customers paying you money. Some of that money can be put back into the sales engine, generating even further growth. As long as there exists a market of willing customers interested in buying your product, it makes sense to continue investing in sales so that you can continue to grow the number of customers.

You might notice that the image above looks a lot like what we talked about a few weeks back when we were modeling the support system2. There’s a stock, which in this case represents the number of customers. There’s also a flow, which represents the sales function of the business. Because customers generate revenue, a portion of that revenue (“investment fraction” in the diagram above) can be reinvested into the sales function to increase the rate of flow into the stock of customers. This cycle causes growth, which is how we know it’s a reinforcing feedback loop. Reinforcing feedback loops want to grow.

Retention, the Balancing Feedback Loop

Peter Drucker reminds us that the purpose of a business is to create and keep a customer. While customer creation exists in a reinforcing feedback loop, the act of keeping a customer—retention—exists mostly in a balancing feedback loop.

While a reinforcing feedback loop wants to grow a stock level, a balancing feedback loop wants to maintain a stock level. In this case, the retention part of the business wants to retain the stock of customers. It does this in a balancing feedback loop. The business sets a target indicator—a desired percentage of customers to retain, in the diagram above—and it invests in retention efforts to maintain the stock of customers in line with that indicator.

Sales vs Retention

Perhaps you’re starting to see what’s behind my cheeky comment that sales has all the fun. As a part of a reinforcing feedback loop, sales is a profit center. It’s (almost) always going to make sense to invest in tools, training, headcount, etc. to make that engine continue to grow.

Retention, as part of a balancing feedback loop, is mostly a cost center3. You want to spend as little money as possible to maintain the stock of customers that you’ve created. Let’s say your goal is to retain 97% of customers. If you can retain 99% of customers with a team of 5 and a 97% of customers with a team of 3, you’ll settle for a team of 3. You want to maintain the desired level of customers for as little cost as possible.

Expansion and Loyalty

Yes, yes, yes, there are reinforcing feedback loops on the retention side of the business as well. First of all, you don’t often hear of “Retention” teams, do you? The hot name at start-ups these days is Customer Experience, which gives us some good signal as to one of the reinforcing feedback loops on the retention side of the business. If a paying customer has a remarkable experience, they’re more likely to tell other people in their network, some of whom may be prospective customers. This creates a reinforcing feedback loop that increases the rate of flow of new customers coming into the business.

The other major reinforcing feedback loop is expansion4. From within your stock of existing customers, several of them may want to purchase additional products and services from you. Take Amazon, for example. They started as a bookstore, but now they sell just about everything, offering customers a greater variety of purchasing options. Amazon also allows customers the option to purchase a better customer experience5, which encourages them to increase the frequency of purchase. Both increased variety and frequency are examples of expansion. These activities are part of a reinforcing feedback loop because they add additional revenue to the business, which increases the revenue per customer, justifying additional spending on activities that increase revenue per customer, etc., etc., etc..

Oh, one more note about the reinforcing feedback loop based on customer experience. That loop is an amplifier whether it’s positive or negative. Delivering a great customer experience can lead to more customers, but if you deliver an exceptionally poor experience, current customers will turn away prospective customers faster than you can create them, driving your stock of customers down to zero. Whoops.

Reinforcing Feedback Loops Are Everywhere

Identifying reinforcing feedback loops is helpful, at least in part, because it can highlight why certain areas of the business are getting attention. Reinforcing feedback loops are the lifeblood of venture-backed business, which have a mandate for growth. Without growth, start-ups fail, so investing in reinforcing feedback loops is critical.

Learning about reinforcing feedback loops can also get you to look for growth opportunities in non-traditional ways. For example, if you look at the product led growth model, growth is driven by building a product that end users love, who then go on to tell their friends, a portion of whom will turn into new paying customers. This model can be so effective that it may make more sense to invest in the product led growth reinforcing feedback loop than the sales reinforcing feedback loop.

What reinforcing feedback loops do you observe in your business?

The next post in this series is about Drift to Low Performance.

I’m drawing a cheeky caricature of sales here, but I want to point out that my colleagues in sales at FullStory are awesome and we’re hiring. They do have tons of fun, but every team at FullStory has tons of fun.

As mentioned in that article, I’m borrowing terminology and concepts from Thinking in Systems, which I highly recommend.

Yes, there’s expansion. That’s covered in the next section just one paragraph down. I had to put a footnote here so you didn’t think I forgot it.

Don’t take my diagram too literally here. Expansion efforts can be driven by the sales part of the business or by the post-sales side of the business. The point is that the function of expansion exists after you’ve created a customer.

Prime is literally a way to purchase from Amazon a better customer experience. Yes, there are other product offerings as well (streaming, music, etc.), but two-day shipping is where it started. Next time you think of justifying if the business should offer an improved customer experience for free, remember that Amazon has a paid tier. Maybe all CX improvements don’t need to be free?